MLB trends: Jacob Misiorowski's velocity is up, Royals homers are down, plus where'd all the wild pitches go?

Let's check in on what's happening around the majors two weeks before the All-Star break

We are more than halfway through the 2025 MLB regular season. The All-Star break is two weeks way and the trade deadline is two weeks after that. Soon thereafter the dog days of summer will set in, then the postseason races will heat up. Fun times ahead. With that in mind, there are three trends worth keeping an eye on as we get deeper into the 2025 season.

Misiorowski's almost unprecedented velocity

Three starts into his MLB career, Brewers rookie Jacob Misiorowski is already a sensation. He's surrendered three hits (two singles and a home run to Matt Wallner) and one run in 16 innings while averaging -- averaging -- 99.6 mph with his fastball. Misiorowski has topped out at 102.4 mph. He's thrown eight of the nine fastest pitches by a starter this season, and 11 of the 13 fastest.

Even in this era of velocity saturation -- everyone throws hard these days -- Misiorowski is redefining how hard a starting pitcher can throw. A starting pitcher just isn't supposed to sit 100 mph, even a live-bodied 23-year-old with little wear and tear on his arm. Pitch-tracking goes back to 2008 and Misiorowski already ranks 15th in 100 mph pitches by a starter.

Here are the starting pitchers with the most 100 mph pitches in the pitch-tracking era:

1. Hunter Greene: 606

2. Jacob deGrom: 321

3. Noah Syndergaard: 325

4. Yordano Ventura: 226

5. Justin Verlander: 205

...

15. Jacob Misiorowski: 62 in 16 innings

Only 11 pitchers have thrown at least 100 pitches at 100 mph as a starter since pitch-tracking launched in 2008. Misiorowski figures to get there by the end of the month, if not before the All-Star break. His slowest fastball in the big leagues is 95.2 mph, comfortably above the 94.0 mph average for starting pitchers. Heck, it's above the 94.6 mph average for relievers.

As if the pure velocity isn't enough, Misiorowski's 100 mph plays up because he's 6-foot-7 and gets 7.6 feet of extension down the mound, a preposterous number. Tyler Glasnow (7.6 feet) and Logan Gilbert (7.4 feet) are the only comparable starters. Misiorowski throws as hard as anyone in the sport and he releases the ball as close to the plate as anyone. It's no wonder hitters are 1 for 22 (.045) against his heater.

There is more to life than velocity, we all know that, but it is a pretty big piece of the pie. Velocity equals margin of error. The faster the pitch, the less time the hitter has to react, and that includes less time to discern a breaking ball from a fastball. When you have to respect 100 mph and start your swing a touch earlier, it's easier to be fooled by a slider or a changeup or anything with a wrinkle.

Eventually we're going to reach the human limit for velocity, right? Pitchers won't continue throwing harder and harder with each passing year forever, will they? Whatever that human limit is, we haven't reached it. Never before has a starter thrown as hard as consistently as Misiorowski. The velocity bar continues to get raised.

Kansas City's home power outage

Every once in a while you come across a stat in this game that stops you cold, and I ran into one this past weekend. The Royals, as a team, have hit 15 home runs in 44 games at Kauffman Stadium this season. One home run every three home games, more or less. Every other team has hit at least 26 homers at home. The Dodgers lead the way with 79 home homers.

To put this another way, the Royals have fewer home homers than Eugenio Suárez (17) and Shohei Ohtani (16), and the same number as Aaron Judge and Cal Raleigh (15 each). Vinnie Pasquantino and Bobby Witt Jr. each have four homers at home. Kyle Isbel and Salvador Perez have two each. Maikel Garcia, Jonathan India, and Drew Waters have one each. That's it. Seven Royals have hit a home run at Kauffman Stadium this year and three of the seven hit exactly one.

"Not good enough," Pasquantino told the Kansas City Star last week, after the Royals lost their tenth straight home game. "And you know, we are continuing to have conversations about why, what can we do to fix it? We haven't yet and that's in the past. We've got a lot of belief in this group, in this locker room, and it's currently not good enough."

Fifteen homers in 44 home games put the Royals on pace to hit 28 homers at Kauffman Stadium this season, and that's me being generous and rounding up. Here are the last five teams to hit 30 or fewer home runs at home in a non-strike, non-pandemic season:

| Team | Year | Homers at home |

|---|---|---|

Royals | 1992 | 24 |

Dodgers | 1992 | 26 |

Cleveland | 1991 | 22 |

1991 | 27 | |

1989 | 27 |

To be fair to this year's Royals, it is only July 2, and home runs typically peak in July and August, when it's nice and hot out. I would expect their home homer rate to increase moving forward, now that they're suddenly going to start banging the ball around the yard like the mid-1990s Rockies in pre-humidor Coors Field.

The thing is, the power outage does not carry over to the road. The Royals hit 43 home runs in 41 road games going into Tuesday's action, a middle-of-the-pack total that nearly matches the league-average 1.11 homers per game. This isn't a team with many big power threats, but away from their home ballpark, the Royals hit a respectable number of balls over the fence.

Kauffman Stadium has never been a good power hitter's ballpark. It's a singles, doubles, and triples ballpark. Statcast's park factors say it has suppressed homers to 82% of the league average the last three years and yeah, that checks out. That they're 20-24 at home and not, say, 15-29 is a minor miracle. It is really, really hard to win games in the year 2025 with this little power.

The decline of wild pitches and passed balls

Other than pitcher, no position in the game has evolved more in the last 15-20 years than catcher. Pitch-framing, which was always a thing but can now be quantified, has moved to the forefront, plus gameplanning is more rigorous and you have to catch so many different pitchers each night and during the long 162-game season. Catchers have so much on their plate.

The easiest-to-see change to the catcher position is the one-knee catching stance, which went from fad to commonplace in about five years' time. These days, Rangers catcher Kyle Higashioka and, depending on the day, Angels backstop Logan O'Hoppe are the only regular catchers to use a traditional batting stance. Just about everyone else uses the one-knee style.

The one-knee stance helps with framing pitches at the bottom of the zone, which is where most pitches are thrown. The trade-off is, in theory, less mobility when it comes to blocking pitches in the dirt. In theory, yes, it makes sense, but it is not playing out that way on the field. Passed balls and wild pitches are at their lowest point in more than 40 years.

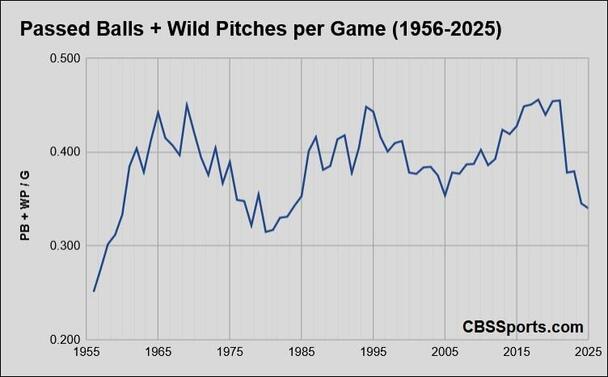

Reliable wild pitch data goes back to 1956. Here is the passed balls plus wild pitches per game rates since then. We're lumping passed balls and wild pitches together because they're functionally the same thing, and oftentimes it's difficult to accurately assign blame to the pitcher or catcher:

There are 0.340 passed pitches (short for wild pitches plus passed balls) per game this season, the fewest since there were 0.331 passed pitches per game in 1983. To put it another way, there is one passed pitch every 26.1 innings this year. It was one every 19.3 innings as recently as 2021. The last year with a lower rate was, again, 1983, when there was one every 27 innings.

Passed pitches per game was 0.455 as recently as 2021. What changed? PitchCom. PitchCom has significantly cut down on the number cross-ups. We can't quantify that -- Statcast doesn't track cross-ups, sadly -- but it does pass the eye test, and it makes sense. No longer do pitchers and catchers have to be on the same page with their signs. It all comes through PitchCom now, which is literally a voice telling the pitcher what to throw and the catcher what's coming.

If the one-knee catching stance makes it more difficult to block pitches in the dirt, it isn't showing up in the numbers, and PitchCom cutting down on cross-ups has more than made up for it. Despite the quality of pitching these days, and the sheer nastiness of the stuff in the game, fewer pitches are getting by catchers than at any point in over 40 years.

![[object Object] Logo](https://sportshub.cbsistatic.com/i/2020/04/22/e9ceb731-8b3f-4c60-98fe-090ab66a2997/screen-shot-2020-04-22-at-11-04-56-am.png)